Since 1889, when the Library Acts were adopted by the Limerick Corporation, there had been a great deal of activity concerning the establishment of a free library. Committees, meetings and focus groups were set up, leading to endless discussion – sometimes heated – about how, when and where to create a free, public library.

In 1892 the Committee identified 1 Glentworth Street as suitable location, entering into a lease for £30 a year. A sub-committee then set about refurbishing the building and finding a suitable librarian to staff it. The latter task proved quite arduous: the interviewers were taken aback by ‘the utter and total ignorance of the men who came before them. They could scarcely believe it possible that in a city like Limerick, respectable intelligent-looking men such as the applicants could be so thoroughly unacquainted with literature.’ Few of them had any idea where the celebrated author Gerald Griffin was born (it was Limerick) and some had never even heard of the literary superstar Lord Byron.[v]

Eventually, after much to-ing and fro-ing, they found the right man: Mr John Hogan. Just past fifty at the time of his appointment, Mr Hogan had led a busy life as a member of the Bakers’ Guild, a trade union official, and a secretary of Limerick Congregated Trades. He also maintained a strong interest in literature and the arts – he was said to be a close friend of the self-styled ‘Bard of Thomond’, Michael Hogan.

Finding the right location was one thing, but filling it with books was quite another. Luckily, the Committee already had in their possession an impressive collection of volumes donated to them some years earlier by Mr George Geary Bennis, a wealthy Paris-based publisher who was born in Limerick in 1793. Although he had achieved great financial success abroad, he never forgot his home city, bequeathing his large private collection of books in English, French, Spanish and Italian to Limerick Corporation ‘for the free use of the

citizens’. After his death in 1866, his books were collected in France by his nephew and returned to Limerick, where the precious collection was shunted from one storeroom to another for years, offering nothing to the public except ever-increasing dust.

The previously-mentioned poet Michael Hogan lampooned the Limerick Corporation for their shameful lack of care of this treasure, writing: ‘A library was sent of late / Bequeathed by a dying man / To the erudite Corporation clan / Poor man, he really did resign / His literary pearls to swine.’

The books eventually made their way into the public’s hands at 1 Glentworth Street, finally fulfilling a dying man’s wish some 27 years after his passing. Over time, more volumes were added, filling nine rooms across three floors. The vast majority of visitors were there to peruse periodicals or newspapers and most people preferred to read in the building itself than borrow books overnight. This may be attributed to the quality and comfort of 1 Glentworth Street compared to the alternative – their homes.

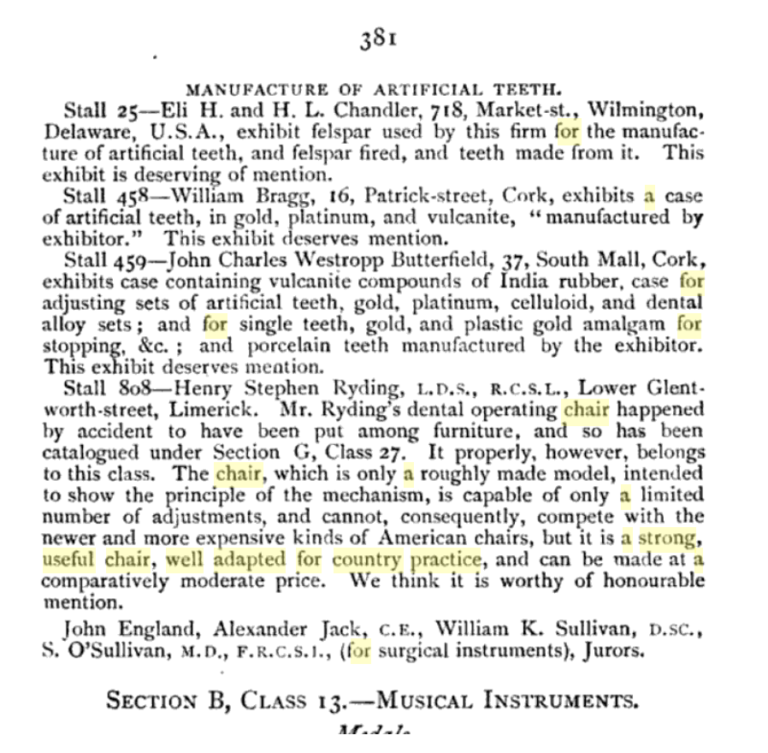

In 1898 the Limerick Chronicle detailed the annual report of the Corporation committee: there were, at that stage, more than 1,000 members, some 291 daily visitors, and over 70 books loaned to ‘home-readers’ every day. That year, the shelves groaned with more than 4,300 books, with history and fiction the most popular choice.

788 books had been purchased at a cost of £150 (carefully selected to guard against ‘objectionable literature’). This meant that each book cost about 4 shillings, give or take. A working man back then earned around 20 shillings a week, a female shop assistant as little as 7[vi]. The free public library offered a vital resource to the hard-working people of Limerick, for whom the simple act of reading a book was a luxury very few could afford.

The Chronicle deems the library a highly successful venture, but already showing signs of outgrowing its location: ‘ladies are practically excluded, there being no place where they might sit apart to read newspapers or periodicals’. It appears they weren’t excluded quite enough for one correspondent with the newspaper, who wrote crossly of having to wait while the lady members’ ‘insatiable appetite for the sensational’ was sated before his ‘legitimate literary-inclined’ needs could be met.[vii]

In the 1901 census, the population of Limerick city was booming, at some 38,000 citizens. John Hogan (58) and his wife Mary (48) were still living at the address, and serving as librarians. The couple did not have any children, and appear to have fully devoted themselves to the task at hand, with opening hours running up to nine o’clock at night.

That same year, John passed away in St. John’s Hospital. In a rare move back then, the Committee voted for Mary to continue in her husband’s stead, with an assistant librarian.

However, her tenure was to be short, because in October of 1903, the foundation stone of a new library was laid by the billionaire Scottish-American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. The building, which still stands at the corner of People’s Park, is now the Limerick CityGallery of Art. Mary Hogan served as deputy librarian to the director of the new library until her death in 1923.